In art there is a long tradition of appropriation—the practice of borrowing what has come before and using that original to engage an old conversation from a new perspective.

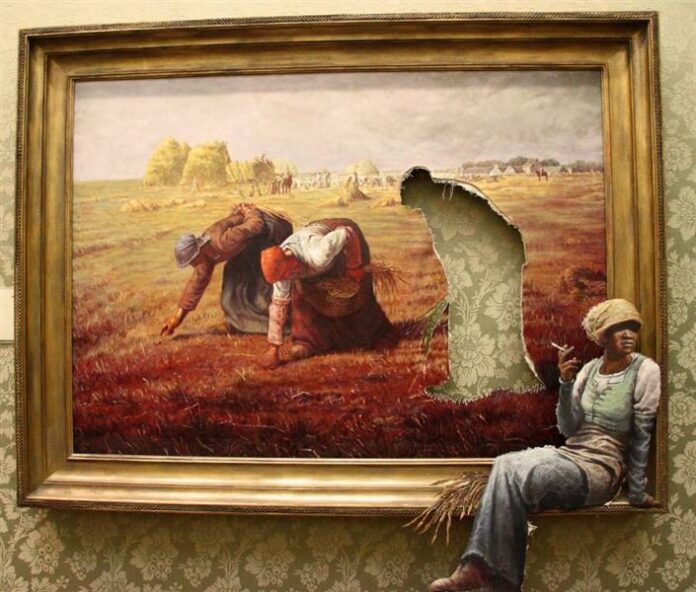

My husband David recently sent me the image of a provocative painting he saw on Facebook. The painting titled “Agency Job”, an oil on canvas created in 2009 by the British artist known as Bansky, is a classic example of appropriation art.

As an introduction to his contemporary conversation, Banksy borrowed “The Gleaners”, the 1857 canvas painted in oil by Jean-François Millet. The original painting describes the activity of collecting leftover corn and other crops from farmers’ fields after the harvest. Millet depicts three French peasant women each involved in one of the three aspects of gleaning: searching for ears of corn, picking them up and tying them together in a sheaf. Their tasks were backbreaking but made an important contribution to the diet of rural workers.

An analysis of “The Gleaners” offered on www.visual-art-cork.com tells us:

“The painting’s focus on the lowest ranks of rural society attracted considerable opposition from the upper classes, who were upset by its artistic pretentiousness and its social radicalism, and linked it with the growing Socialist movement. ‘The Gleaners’ was however accepted for display at the annual Salon of the Academy and was greatly admired by French republicans for its dignified and realistic appreciation of the rural poor.

Millet paid close attention to the ‘Gleaners’ composition, using artful devices to imbue his subjects with a simple but monumental grandeur. The angled light of the setting sun accentuates the sculptural quality of the gleaners, while their set expressions and thick, heavy features tend to emphasize the burdensome nature of their work. Furthermore, these figures, bent double and toiling in the darkened foreground, are set against a warm pastoral background scene of harvesters—with their haystacks, cart and sheaves of wheat—reaping a rich harvest. The contrast between abundance and scarcity, and between light and shadow, is cleverly used by Millet to emphasize the class divide. And the remoteness of the landlord class is also highlighted by the blurry image of the landlord’s foreman, sitting on a horse in the remote distance (right).”

Appropriating “The Gleaners” for his own artistic purposes, as though tearing a page out of history, Banksy left a raw-edged hole in Millet’s painting when he removed one of the bending women and repositioned her. “Agency Job” features Banksy’s cut out of the woman smoking a cigarette as she takes a break from her field work while sitting on the frame of Millet’s painting. By way of his 2009 appropriation and alterations, Banksy created his contemporary spin and social comment on an age old theme—the plight of those seen as an underclass.

The conversation Bansky broached over a decade ago is once again in media headlines and in the chants of protestors—“Black Lives Matter!” Banksy insists we pay attention. When we do pay attention we will see and find Millet’s original message.

“Millet had been deeply affected by the 1848 revolutions and their promise of democracy. Becoming the first European painter to portray the peasantry, a doomed class impoverished by advancing capitalism, he was castigated by the bourgeois class.”

“Millet had been deeply affected by the 1848 revolutions and their promise of democracy. Becoming the first European painter to portray the peasantry, a doomed class impoverished by advancing capitalism, he was castigated by the bourgeois class.”

In Millet’s calm imagery of the “Gleaners” he declares that there are signs that the world can be changed into a better place—that change is coming. The white vest and red and blue hats of the gleaners form the three colours of the Tricolour—the flag of the French Republic and the symbol of popular Revolution in France – as captured for instance in “Liberty Leading the People” (1830) by Delacroix.

For us as citizens of a nation that flies the Red, White and Blue, is not Bansky offering the same message delivered by bold French artists almost two centuries ago?